Evolutionary ecology of ecosystem resilience

Although environmental change triggers both ecological and evolutionary responses, the framework used to assess ecosystem resilience has lacked the evolutionary component thus far. To address this gap, I have developed the first generation of ecosystem resilience models that include evolutionary processes.

Bifurcation tipping, the current paradigm in ecosystem resilience

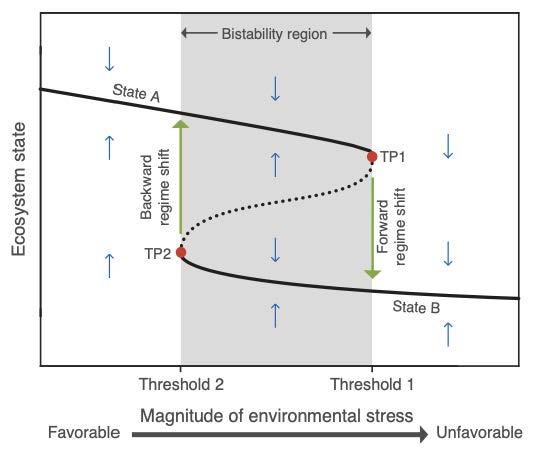

According to traditional ecological theory, when environmental conditions are favorable (i.e. low environmental stress), the ecosystem is in the upper branch (State A in figure 1). If conditions gradually deteriorate, the ecosystem follows the stable equilibrium line until conditions exceed threshold 1. At this point (TP1), the upper stable equilibrium disappears, and thus a slight increment in the magnitude of environmental stress causes the ecosystem to tip to the lower branch (State B). Most efforts to prevent ecosystem regime shifts therefore focus on maintaining environmental stress below a safe magnitude, in this case, below threshold 1 (TP1). If this magnitude is exceeded, to restore the tipped ecosystem, it is not sufficient to reduce environmental stress below threshold 1, but to a much lower level of stress indicated by threshold 2 (TP2). Once the magnitude of environmental stress is below threshold 2, the ecosystem quickly recovers back to State A.

A paradigm shift in ecosystem resilience

I, with a diverse group of collaborators, discover that the introduction of trait dynamics mediated by evolution violates this paradigm in different manners:

First, regime shifts may occur despite the critical threshold is not exceeded by environmental stress: We showed that a change in environmental conditions that does not exceed a critical threshold (e.g. TP1 in figure 1) may trigger an evolutionary process that, after a substantial delay, results in a regime shift. Our analysis revealed that ecological processes alone cannot predict the occurrence of these evolutionary-induced regime shifts (Chaparro-Pedraza, P.C. and de Roos, 2020), which can result in unintended management outcomes of wild populations (Chen, R., Chaparro-Pedraza, P.C., et al 2023).

Second, evolution may prevent a fast ecosystem recovery once environmental stress is reduced: we showed that, once an ecosystem tips to an alternative stable state, evolution can enable species to adapt to the conditions of this state (e.g. State B in figure 1). After the reduction in environmental stress (e.g. below TP2 in figure 1), it may take long time for them to readapt to the original state, causing a significant delay in the recovery of the ecosystem (Chaparro-Pedraza, P.C. et al, 2021).

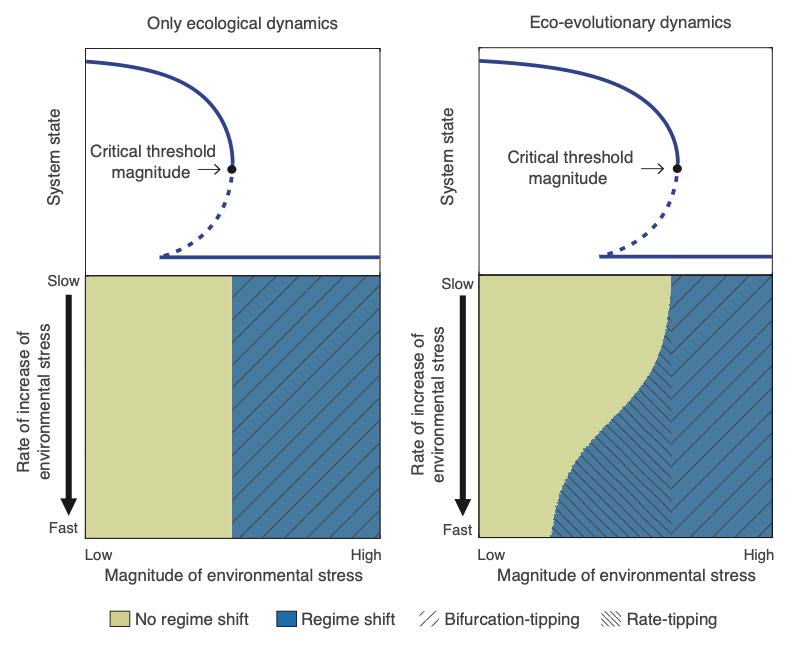

Third, eco-evolutionary feedbacks can render ecosystems susceptible to Rate-tipping (figure 2): Previous work had hypothesized, without formal proof, that evolution may facilitate adaptation and thereby shift the magnitude of a critical threshold (threshold of Bifurcation-tipping, e.g. TP1 in figure 1) in ecosystems, perhaps delaying regime shifts. I provided the first proof to this hypothesis, and demonstrated that although the introduction of evolution may indeed delay regime shifts caused by Bifurcation-tipping, regime shifts can occur much earlier due to Rate-tipping (Chaparro-Pedraza, P.C. 2021).